My experience of viewing Waiting For Godot at the Haymarket Theatre, performed by four iconically important actors of our time, Ian McClellan, Patrick Steward, Ronald Pickup, Simon Callow, left me wondering what I had hoped to gain from viewing the play. You see, I have always prided myself as the type of theatregoer who consciously retained a ‘niave’ perspective. This is despite viewing hundreds of plays and writing thousands of words on experiencing live theatre. Every time I walk into a theatre, I’m excited by the prospect of being ‘taken’ somewhere I never imagined going to, visiting ideas, concepts and feelings in ways that I might not normally have done so.

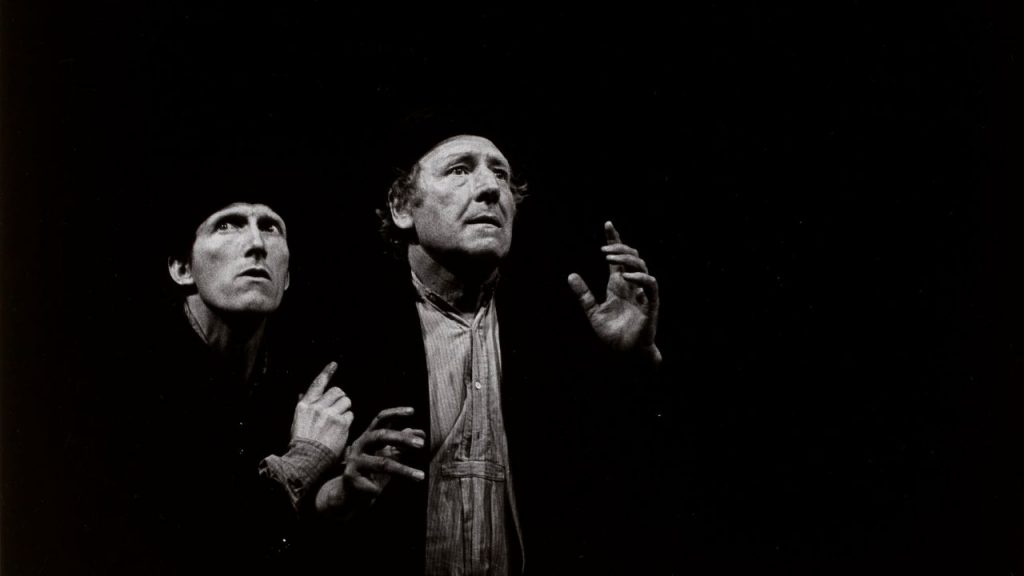

Waiting for Godot, Octagon Theatre University of Western Australia 1984

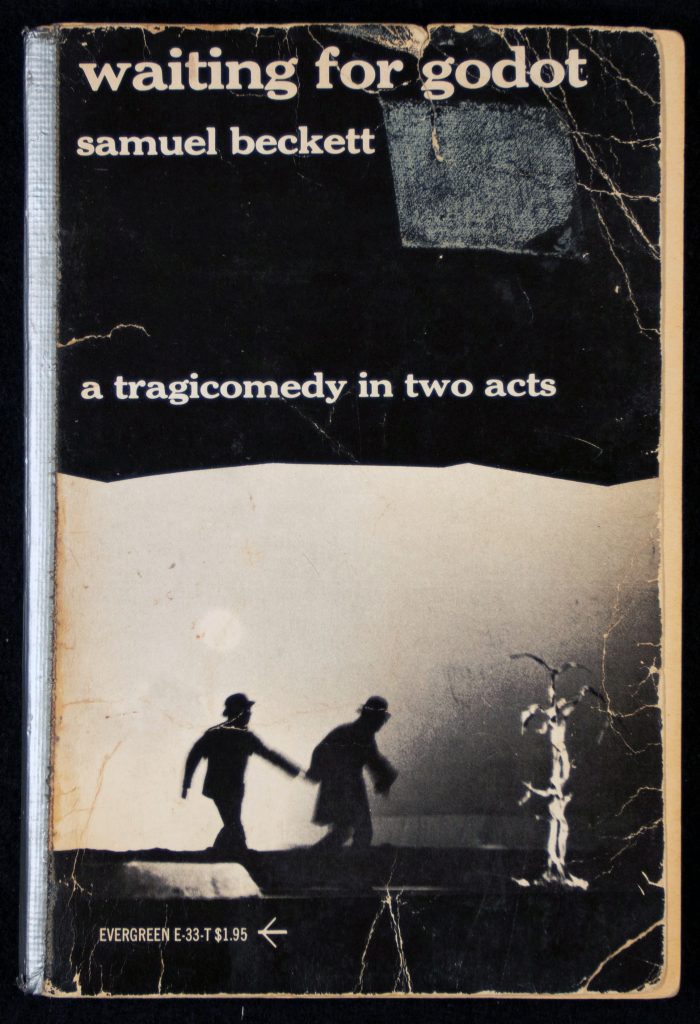

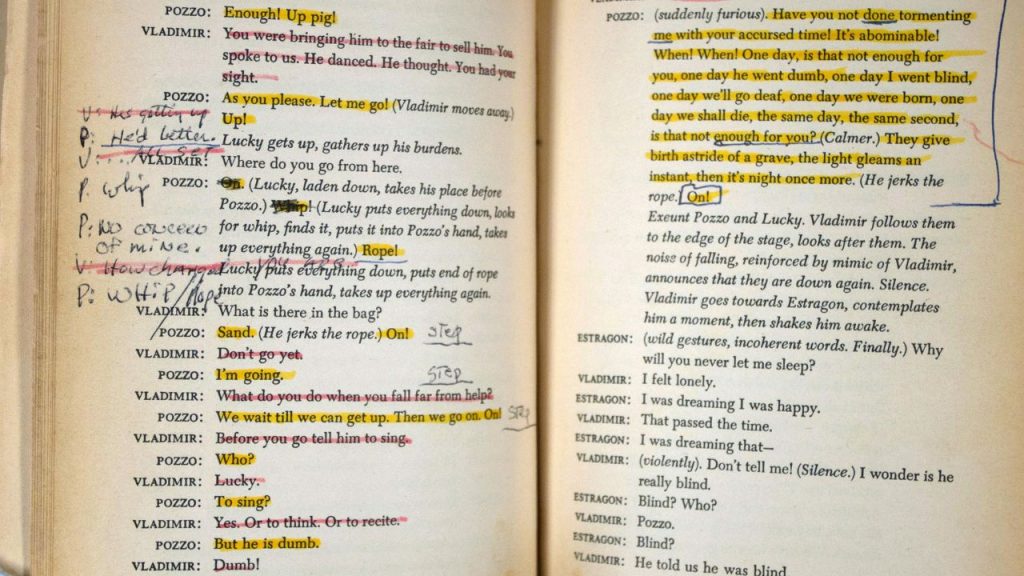

In early 1984, Cluchey’s San Quentin Theater Workshop was invited to perform Waiting for Godot at the Adelaide Festival in Australia, but funding for both the trip and the production was predicated on Beckett being involved. As a compromise, Beckett agreed to oversee a staging directed by his friend Walter Asmus, who had served as his assistant director for the 1975 Berlin presentation, and for two weeks he supervised rehearsals at Riverside Studios in London, with Cluchey playing Pozzo. This prompt book directly reflects the significant, Beckett-generated emendations the author made to the 1975 version, and includes additional notations and alterations.

As a young teacher, I had gone on a school outing to view the production of Waiting For Godot in 1984 by none other than the San Quentin Group. At the time, I was totally ignorant of the production’s importance or its history of coming into being under Beckett’s directorship. Beckett’s authority and his choice to work with the San Quentin prisoners literally took me to another place.

What I experienced that night lives in me still. The characters calling out from the stage. The experience of waiting and moving, in the memory of devastation in which people still talk about living amongst the ruins. Their expectation of feeling hopeless mingled with my own reactions to academic ways of viewing despair and pointlessness, hunger and death, the poetics of resonating words of the embodied language.

I didn’t plan to compare my viewing of Samuel Beckett’s own production with the San Quentin Group with the one before me at the Haymarket. But I found myself doing so more and more as the production went on: why did Didi so quickly and swiftly forget about the pain in his genitals? Why was he so cheerful all the time? Why did Estragon and Vladimir seem so fearless?

The 1984 production of Godot remains one of the most visceral experiences in the theatre that I have ever encountered. I don’t believe I have ever felt pain so palpable as I did that evening: I wanted to scream but all I could do was ‘gawk’ at the stage images. I wanted to escape but all I could do was witness the futility of the lives being depicted. Yes, as I heard the attempts of creating ‘patter’ and watched the effort needed to move painfully – feet, genitals, hats and back to feet.

But the Haymarket production with its stars, to my mind, chose to minimise the pain – all kinds of pain: physical pain; psychological torture of living in ‘cycles of time’ – a day, year, the boom/ bust capitalist economy, peace and war, famine/ plenty; the foolishness of setting a course in time based on a particular technique; the acknowledgement of the size of man-made disasters shown through two world wars and various economic meltdowns.

Instead, the 2009 production chose to highlight the clever patter and the choreographed movements of the tap dancers and the physical tricks of vaudevillians – a sense of what we now think was vaudeville and not what it actually may have been; energy for energy’s sake, art for art’s sake. No hint of irony and resonance with the ‘real’ context: for instance, the audience laughed at the moments the actors referred to the audience as ‘bog’ but I noticed that the script was edited so that the actors did not refer to the audience as a ‘charnel house’

So, I looked at ‘stars’ and not at Beckett’s characters: they were not hungry – no consequence to the deprivation – they went off stage to ‘rest’. I didn’t believe their physical pain: Pickup’s muscles didn’t seem to ache, none of the characters seemed to be ‘in danger’. No one seemed to be held in the tension or the depth of silence like I experienced when I confronted the San Quentin Group. This was a no-nonsense production that had made sense of the play which Kenneth Tynan had judged to be saying ‘nothing’ twice!

My paraphrasing of the experience went something like this: two old men – Estragon and Vladimir (Gogo and Didi)– with Gogo on the verge of Alzheimer’s and his cheerful and caring friend Didi trying to cheer him up at a time when they are down on their luck. When they come across the somewhat cruel spectacle of a slave and master they are given a lesson on ‘things are not what they seem’. In a poststructuralist flourish, the audience might imagine that slaves just like being slaves and slave-owners just carry the unbearable burden of keeping the slave alive for such a purpose.

Playing in the space seemed limited to a circle in the centre of the Haymarket’s vast stage and, while there were references to particular objects, for example, the tree & and ditches off stage, the production might have well been enacted in a void. There did not seem to be a ‘visceral’ connection between the characters and the destroyed landscape in which they were situated. The location seemed to hold no threat to them as they seemed jolly most of the time and only ‘annoyed’ that they couldn’t go anywhere because they were ‘waiting for Godot’.

Godot 2009 left me with many Questions

Questions about acting technique – why did the actors do this and not that – for instance, why did Patrick Stewart have sore genitals one moment when he’s pissing and then came on stage apparently pain-free and then sit cross-legged on the stone seat?

Questions on how ‘stars’ have such a powerful status – beyond and above their own art form: the cult of personality firmly defining them. By contrast, I remembered, when I watched Cate Blanchett play Hedda Gabler in 2004 when I concluded how she was a great actor because it took only about two minutes for me to ‘forget’ the star and view the Hedda she created by playing her as the most unsympathetic Hedda imaginable. It was only when the gun goes off at the end of the play in Hedda suicide scene that I acknowledged the power of Blanchett’s performance and her unrelenting pursuit of Hedda’s desperate life.

However, I rarely stopped thinking of the four actors as anything but their personalities except for feeling that occasionally Ian McClellan ‘hit the mark’ in the first act and that Patrick Stewart did the same in Act 2 when he confronts the boy and begs to be acknowledged as a person; I felt it when Ronald Pickup delivered Lucky’s speech which moved me and that Simon Callow just overacted for the first act and only hit the enigma of his role in the second act through being literally blind?

I didn’t believe that any of them were waiting for anything: that is, they didn’t show what it meant to miss your moment to be someone creative, productive and ennobled, what it meant to even believe in such a prospect in the face of the overwhelming evidence that so many people have failed to attain a meaningful life.

Who am I to say this?

An unknown theatre historian who had come to London to re-think her own place in teaching, researching and creating theatre. I was so excited at the prospect of seeing the production – the £47 I spent on the tickets is the most I’ve ever spent on tickets. I read the reviews, and seeing the favourable reactions, I concluded that it must be a monumental interpretation of a most challenging play. I so wanted to see how four notable performers dealt with the central problem which the play presents for actors of not acting, of doing nothing but wait.

After the show, I thought, maybe I got it wrong. Maybe Godot isn’t about waiting but how we can’t wait. We jump about from one experience to another and our hell is paved by our good intentions.

So what was I expecting?

I think that I was looking for the insights I’d experienced in the 1984 production which under Beckett’s direction portrayed how theatre was not about talking but listening, not about showing but observing – the auditorium / the theatre – the listening place and the seeing place. The courage of waiting, waiting for a long time, for an unreasonably long time, for virtues to be realised and sins to be redeemed. There is so much terror in the image of giving birth astride a grave. Why not deny it and keep as jolly as our four stars dancing on the Haymarket’s stage?

Our minuscule lives in the face of overwhelming and uncontrollable forces – hardly the way to a Box Office success, hardly the way the play could achieve popularity – hardly the way it gained its effect in the past – if Beckett’s own productions are anything to go by. In the relatively long distance in time between ourselves in 2009 and the experiences of total calamity brought about in European history between 1914 and 1945, we are now confident enough to seemingly redeem Beckett’s less entertaining version of the play with a more upbeat one, we can lighten up and laugh off our nihilistic tendencies with a soft shoe shuffle. After all, ‘the troubles’ are all in the Middle East and Africa and Asia and all we need to do is better protect ourselves against those terrorists who would like to make violence on a global scale.

In any case, we have a hard enough problem keeping up our considerable advantage in world affairs. It’s tough getting our heads around our part in global warming or monetary and financial failures or spreading democracy. Only such a short time ago we had unprecedented economic growth in the West, while we promised to look at the systemic nature of children living in poverty and other inequalities everywhere else. And why do we need to have any agency ourselves? Our performance culture dominated by stars and their interesting stories to occupy our lives. We have stars through whom we live vicariously and experience their great success in answering the big question. Their success IS our success. That’s the truth, isn’t it?