J’ai Deux Amours: The Josephine Baker Story

Genre: Musical Theatre

Venue: Etcetera Theatre 265 Camden High Street London NW1 7BU

Low Down

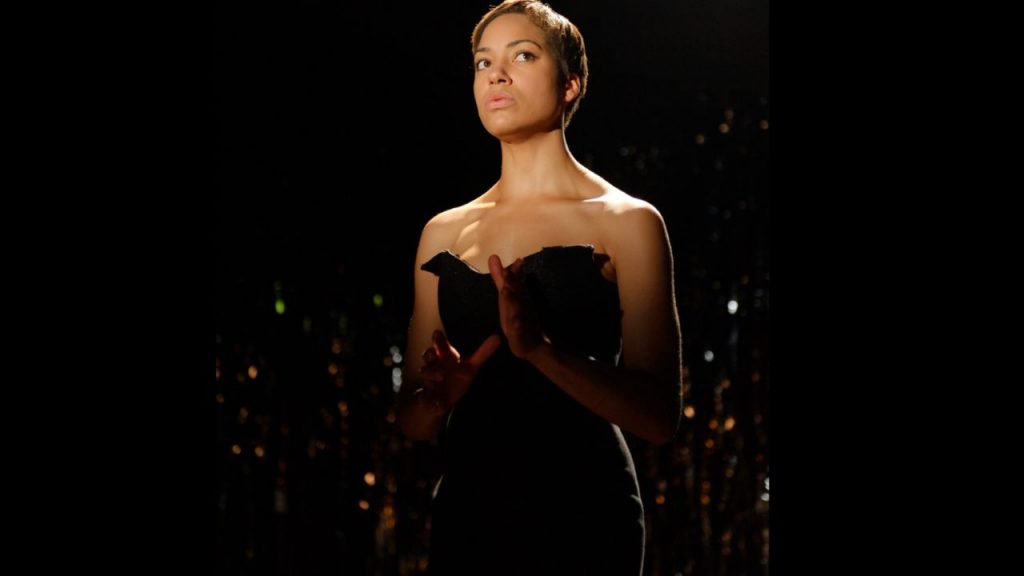

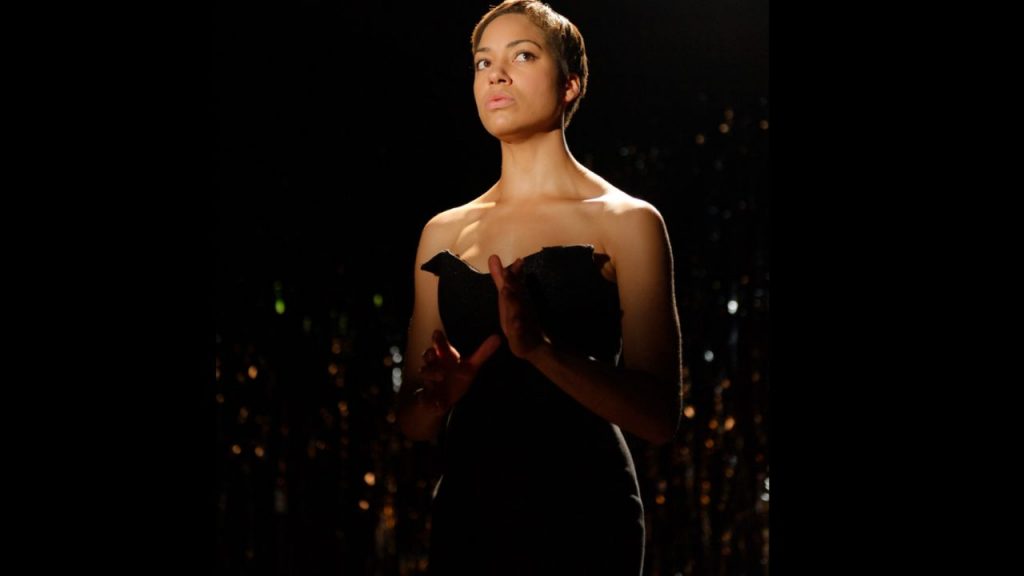

Cush Jumbo received a standing ovation from many members of the audience at the Etcetera Theatre on the opening night of her one-woman show J’ai Deux Amours: The Josephine Baker Story. There were many good reasons I could see for this: her great singing voice, her versatility in taking on different characters while telling Josephine Baker’s biography and, above all, her engaging energy. While acknowledging these qualities, however, my reaction to her presentation of Josephine Baker herself was less enthusiastic: mainly because in the end I felt that I came to know and feel little more about Baker than I’d already pick up over the years about her extraordinary life in both America and France – her Deux Amours.

Review

As previous critics have noted, Cush Jumbo is clearly one of London’s great young actors. Her versatile performance skills show an all singing, dancing and acting talent with high energy and tremendous focus and concentration. But on choosing Josephine Baker as her subject she chose a subject who continues to be difficult to contain in any story depicting her rise to fame. For this reason, Cush Jumbo’s depiction of Baker, virtually from the start of her life in a childhood of poverty to just moments before she dies at 68 as an extremely famous person, is extraordinarily ambitious.

The encounter between ‘the young woman from Lewisham’ watching the glamorous star on the screen at the start of the show holds the delightful promise of a personal relationship between two ambitious women which I thought was about to be explored: but once the switch is made into the Josephine Baker role, the young English girl is forgotten until the end. In her place, Cush Jumbo performs Baker largely in chronological sequence, after enacting her acceptance speech on being awarded the Croix de Guerre, Légion d’Honneur and Rosette of the Résistance for her bravery during WW2 and another scene in which she is refused entrance through the front door of New York’s Rosemount Hotel. The Rosemount Hotel scene is particularly strong in the way it shows racism as a kind of skin-prickling and gut-wrenching physical attack on her person as she listens to the porter’s request that she use the back entrance.

After this, the chronological sequence shows a poignant portrayal her parent’s turbulent relationship and how her mother sees young Josephine as competing for her husband’s affections. Dressed in a dirty, ragged non-descript gown, young Josephine McDonald ‘dances’ through her story as she watches her sad mother lives on tiny ‘little bits of happiness’ of the occasional soft embrace from her largely absent partner.

From this point onwards the scenes come as a series of ever climbing moments to success and fame: her job waitressing at The Old Chauffeur’s Club; her first marriage to Willie Wells, then her pregnancy and delivery of a stillborn daughter at 13; her subsequent divorce from Willie and return to work at Chauffeur’s Club and meeting her second husband, another Willie but this time Willie Baker, from whom she receives her famous surname. At this stage of the show, the audience receives an exhibition of Cush Jumbo the versatile dancer of tap and chorus line as she tells the story of moving from dancing on the street to a small theatre in St Louis to a stage in New York and then to Paris.

The rapid succession of scenes is dizzyingly rapid and I felt that the show could have benefited from changes of pace. Instead, the showy energy minimises some extraordinary facts of Baker’s life in order to get across the broad expanse of her life. Most alarmingly, as a writer Cush Jumbo normalizes Baker’s early sexual experiences, marriage to someone fourteen years her senior, followed by pregnancy and the birth of a stillborn daughter as a kind of ‘step one’ and the bottom-most rung of climbing the ladder towards her fame. In fact, nothing about her sexuality – her promiscuity and bisexuality – is dealt with in any substantial way. I recognize the problems of what material is included or cut from a biographical performance project. But why, for instance, do Josephine Baker’s two American husbands get presented to the audience and not her two subsequent European ones – Frenchman Jean Lion (from whom she attained French citizenship) and French orchestra leader Jo Bouillon in 1947 (who helped to raise her 12 adopted children)? Couldn’t these relationships have served in further exploring J’ai Deux Amours and Baker as an American and a French citizen?

Perhaps the most problematic treatment in the show is Cush Jumbo’s handling of La Baker’s ‘savage’ nude dances that was the reason for Baker’s notoriety in the first place. The strength of describing the dance through its rhythmic beats is again promising. Yet, the question of nudity itself is passed off in American sitcom fashion as an outraged Baker comes to terms with the word ‘nude’ spoken through the speech inflections of her French theatre manager. To suggest that Baker was innocently caught up in the world of the Paris nightlife is not sustainable: nudity is at the heart of Josephine Baker’s performance history and inseparable from the subject of skin colour and ethnicity. Josephine Baker, the Amazonian statuesque woman on screen that we view at the end of the play is a jolt to the senses, one which reminded me how different she was from the innocent and polite portrayal of her which Cush Jumbo gives us in her rendition.

Undoubtedly, Cush Jumbo has ample material to create an entire musical on Josephine Baker’s life. As it is at present, the show is worthy viewing becauseof the extraordinary talent of Cush Jumbo herself. I look forward to seeing if she can realize more of the complex and problematic Josephine Baker in the next version of her project.

Reviewed by Josey De Rossi Tuesday 20 September 2011

Website :

http://etceteratheatre.com/