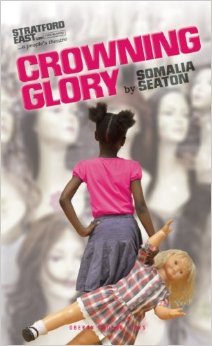

Women v Hair: Crowning Glory at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East

This story of race, gender and hair will see you laugh, cry and fume, as an unflinchingly honest portrayal of black women dissipates the myth that we live in a post-feminist age. Explosive drama. At the Theatre Royal, Stratford East.

If you attached a Geiger counter to Somalia Seaton’s Crowning Glory, it would break the dial. The drama radiates energy, each part colliding and moving ever outwards to encompass a monumental blast that explodes the myth that we live in a post-feminist age.

Seaton presents the play as an entertaining kind of Brechtian Lehrstucke, or “learning play”, showing that the black woman’s struggle to tame her hair (with scarves, wigs and a multitude of hair products) is part of the core of her existence. The play’s seven characters present a series of first-person narratives, sometimes stylized as poetic verse, which are broken up by third-person commentary, also delivered by the characters. I found the effect utterly engaging. The contrasting personal and public worlds in which Seaton’s women exist are called up beautifully.

For instance, there’s “Pickyhead” (Toyin Aydun-Alase), part mother, part fidgety little girl, craving to be let out to play. Her monologue comically shows how it is the black mother’s fears for her “ugly” daughter that set in motion a lifetime of worrying about self-image, and what is acceptable.

Then there’s “Bounty” (Rebecca Omogbehin), a highly educated woman who gives the audience her private reactions to her public argument with other black women who criticize her for successfully integrating into a white European lifestyle. Other stories by the mixed-race “Halfbreed” (Allyson Ava-Brown), “Panther” (Lorna Brown), “Haircomb”(Sheri-An Davis) and “Bal-Ead” (T’Nia Miller) also show the public and private dimensions of women who are questioned, insulted and abused for their African looks and hair.

The play shows how many contradictions are at work here. It suggests that African women are more likely to suffer from put-downs and mistreatment from their own families, and that as young girls mature into womanhood, they often face rejection from black men who see them as less attractive than the smaller and more petite white girls they pursue.

However, Seaton shows us that women can grow stronger through adversity, through physical self-assertion and mental resistance to imposed images. So, while the play begins with the little girl “Pickyead” it ends with the Amazonian figure of Bal-Ead, dressed in red and black lingerie, who confronts her husband’s disapproval with dignity and strength.

This all-woman ensemble is very well directed by Dawn Reid, while Nick Barnes’s set design is highly inventive in underscoring the themes of the play, with multi-level angular platforms giving the effect of different kinds of pathways climbing ever higher. At one point, the levels turn into the shelving of a hairdresser’s shop comically displaying wig-wearing mannequin heads.

The play makes use of projection and film, disrupting the live performance with snippets of real women talking about their lives, their hair and the idea of beauty. Other filmed excerpts are fictional, as cast-members portray either self-advertising clueless women, giving make-up advice on YouTube, and or opinionated men, vocalising their judgements on women.

Although Seaton goes some way in revealing the shallowness of the idea that white women bear some ideal of beauty, and are more liberated than their black women, she reserves her sharpest barbs — in a play about race and gender — for black men. There is not an enlightened, sensitive black man in sight. Even Michelle Obama appears in the filmed projections without her husband. Black men are consistently referred to as wife deserters, absent fathers and crude lovers, whose egos seem unconstrained by family rules or social expectations.

That such men exist is indisputable, but the one-dimensional view of them doesn’t sit well with the ironies, contradictions and humanity of the rest of Crowning Glory. I feel that Seaton could rework her presentation of them to incorporate some of the subtleties of character which make her female characters so appealing.

Date reviewed: Tuesday 22nd October 2013