Venue: Union Theatre 204 Union St, SE1 0LX

Low Down

Invariably, the choice of whether a play is rarely or often staged both make the claim that the play is relevant for ‘our times’. Of course, that’s the point. As the audience lives in the here and now, Phil Willmott’s realisation of Shakespeare’sKing John clearly how Shakespeare remains our contemporary. I saw this particularly in way that the production engaged the audience in its psychological depiction of warfare and its exposition of how spiritual and temporal claims live in the figure of the king.

Review

Nonetheless, the fact that the theatre poster pointed out it was 10 years since King John had been produced by the RSC in 2001 very much of interest. Pointing out any production’s novelty is good marketing, and in this case calls on audiences to engage in fathoming why or why not the play might have been overlooked: what view of kingship and political leadership might it reveal? What contemporary view of politics might be layered over its 400-year-old drama showing a society grappling with a belief in the divine right of kings?

On the night I viewed the production, it seemed to me that the strength of Phil Wilmott’s realisation of this infrequently staged Shakespearean classic came through its war-mongering matriarchs, King John’s (and Richard the Lionhart’s) mother Queen Eleanor, played by Maggie Daniels, and his sister-in-law, Lady Constance, played by Samantha Lawson. Both portrayals were superb: their physical presence, movement and commanding voices engendered the tensions of Amazonian warrior figures trying to eek out of themselves the tenderer and more domestic image of ‘mother’.

Another subplot brought vividly to the audience’s attention is that of the conflict between warring brothers, epitomised through Phillip the Bastard and Robert Faulconbridge, portrayed by Rikki Lawton and Leonard Sillevis respectively. The partnership seemed to me a precursor of Edmund and Edgar in King Lear, and while legitimacy vs. illegitimacy is taken through particularly dark ironic twists in Lear, which was written 11 years after King John, the importance of the theme is absolutely established through Lawton and Sillevis. Rikki Lawton’s creation of a buffoon-like manipulator is very strong. His dubious moral intentions throughout the play makes the final lines he speaks in the play an ironic statement on the ironic foundation of ‘englishness’ itself.

Two more aspects of the production seem to engage the audience further. One was the role played of the ‘young royals’ seen through the characters of Louis, the Dauphin, young Henry III, Blanche and Arthur. Phil Willmott’s direction ensured that these never looked like ‘small parts’: on the contrary, their dramatic importance was set through his detailed reading of the play by ‘actioning’ (as he explains in the theatre programme) and through the talents of the young actors themselves.

The other aspect that was most engaging was the play’s exploration of friendship and blind obedience. The Dauphin’s friendship to King John, Blanche’s and Louis’s love and marriage, Hubert’s loyal obedience and consequent disobedience to King John and, even more poignantly, young Arthur’s love of Hubert, his jailor-turned-protector. Each of these relationships held surprises through their turning away from conventional (and obvious) enmities and enforced loyalties: instead, the acting out of the relationships were themselves the reasons for falling in and out of war or securing fleeting moments of peace. By contrast, the only really tyrannical portrayal of authority presented in the play came through the character of the gluttonous Cardinal Pandulph, who, as the Pope’s representative, commanded excommunications at will. Through this, the audience encounters the political devastation of religious-based wars, then the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and now the War on Terror.

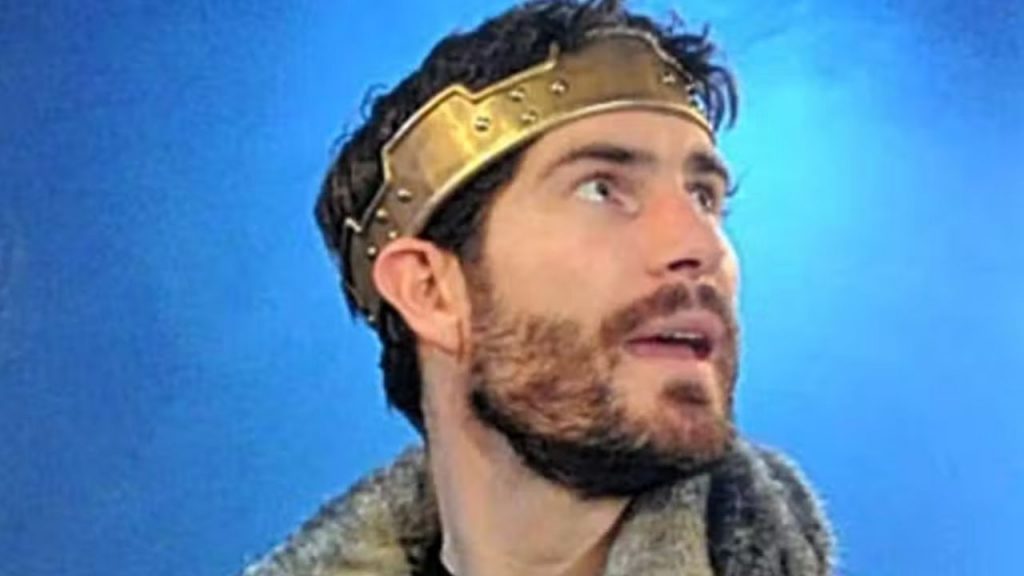

At the centre of the wars, relationships, filial competition and matriarchal belligerence stands King John and his counterpart the French Dauphin. In both cases, the two actors playing these roles portrayed their characters’ weaknesses and vulnerabilities. If King John stood for anything, he represented the impossibility of fulfilling the role of monarch. It seems just too big a part for him. It seems to me that Nicholas Osmond achieves his part by focussing on anachronistic contemporary gestures and vocalisations to emphasise King John’s disjunction with his own time and place. I enjoyed the levity and insecurity it caused in the audience around me. Are we really supposed to laugh at such a monster? How could such an ineffectual man survive in ordinary circumstances, let alone as King of England?

Technically the production I is also impressive: Emma Tompkins imaginative designs deserve applause. The lighting design created the atmospherics of stately rooms, battlefields, tall fortresses and dark prisons in King John’s world.

Such an effective realisation, however, leaves me wondering why Phil Willmott, his talented cast and creative team did not further edit the scenes of the second half of the play, particularly those in the seven scenes of Act 5. To my mind, it desperately needs to be reimagined to prevent the unravelling of the tensions so carefully set up in the first half of the show. I would further suggest that not even the clever use of a macabre waltz dispelled the feeling that the scenes with the English rebels just lacked the vitality of earlier scenes between the English and French.

Still, there are so many brilliant moments in King John that I have no problems recommending it to anyone, familiar or not with Shakespeare’s more frequently staged histories.

Reviewed by Josey De Rossi 25th January, 2012

Website :

http://www.uniontheatre.biz/

http://www.kingjohnplay.com/

Show runs to February 11. I just looked at the Union website and the tickets are selling fast!