Indigeneity in the Contemporary World

Theatre historian Josey De Rossi, who has studied the effects of European cultural imperialism on indigenous art forms, guides us through some of the themes raised by this unusual cross-arts project. At the Bargehouse.

I arrive at the Bargehouse sufficiently early to view the four floors of installations and displays by contemporary artists from North and South America, Australia, the Pacific and South Africa, before the performance of Masi Maiden begins. This is EcoCentrix: Indigenous Arts, Sustainable Acts, and the collection is the result of the Indigeneity in the Contemporary World Project led by Professor Helen Gilbert of Royal Holloway, the University of London which is funded by the European Research Council. Professor Gilbert is also its curator, assembling the works of indigenous artists with international reputations, such as Australia’s Bangarra Dance, Quechua filmmaker Irma Poma Canchumani and Canadian-based Tahitian artist Peter Morin.

As I move about the different rooms, I see examples of traditional indigenous art forms finding ways of sustaining artists and communities, for instance, how filmmaker Irma Poma Canchumani’s finely etched gourds (pumpkin-like shapes) are transformed into storyboards through the use of the detailed carvings as the ‘scripts’ for the films that she produces.

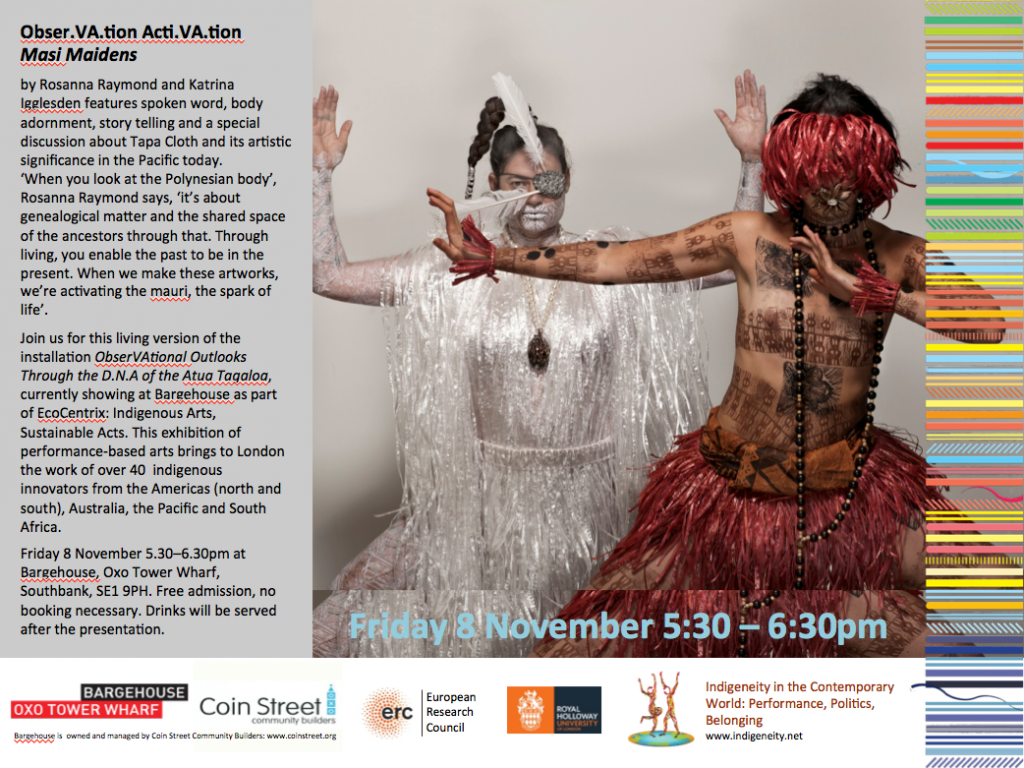

By the time the performance begins, I recognise that Masi Maidens is the work of internationally established author and Pasifikan artist, Rosanna Raymond, and her co-performer, Fijian/Canadian performer, Katrina Talei Igglesden. The performance is also a living version of Raymond’s visual arts installation in EcoCentrix of ‘ObserVAtional Outlooks Through the DNA of the Atua Tagaloa’.

This transformation from visual arts installation into performance takes the audience on a journey of exploration, sharing with them what it means to be culturally and genetically linked to an indigenous ancestry. Specifically for Raymond, of Samoan descent, and for Igglesden, of Fijian ancestry, this is shown through the Polynesian traditional craft of making and designing Tapa Cloth from the bark of the Mulberry tree. Women throughout the Pacific bring to the craft their own ‘spark of life’ or ‘mauri’ as they create location-based original patterns and earthen-colour schemes.

Rosanna and Katrina choose to manifest the ceremonial cloth as full body drawings: effectively showing the creative potential of the Tapa cloth tradition working with the context of the performance as a living symbol of cultural exchange between performer and audience. I notice, however, that the elaborate patterns covering their bodies don’t look like stage makeup but ‘naturally’ complement the performers’ own Polynesian appearances.

The performance, in fact, begins outside the Bargehouse and, like a religious procession, moves through every room on all four levels of the Bargehouse. For this, the performers use styled actions and sounds that at first seem like stereotypically tribal incantations. However, their specific interactions with various spaces soon change this impression.

When the two performers finally arrive on the third-floor performance space, they enter from the stairwell side at the back of the large room. They break into a gliding form of goose-stepping that is perfectly synchronized. More impressive still, the contrast between Rosanna’s white stringy tunic and Katrina’s red-earth feathery one seem exquisitely balanced in every way: the performers are earth and sky, mammal and bird, the dark and the light.

Then, in the centre of the performance space, Rosanna begins to speak like someone presenting a very personal and particular truth of her lived experience as a Polynesian woman. Her poetic language builds into an epic tone as it resonates with her stylised movements and gestures. Sometimes she uses familiar Haka gestures and at other times Katrina uses equally identifiable bird-like movements but mostly, the words and movement remain highly original.

They end by affirming the complementary nature of the two personae share, after which there was a post-show talk. I would have liked more of the performance and for it, and for the exhibition, to be left to speak for themselves. Running at just 30 minutes, there were certainly enough ideas to make a much lengthier performance. At least there’ll be plenty more similar events to look out for at the same venue in 2014.

Date reviewed: Wednesday 13th November 2013