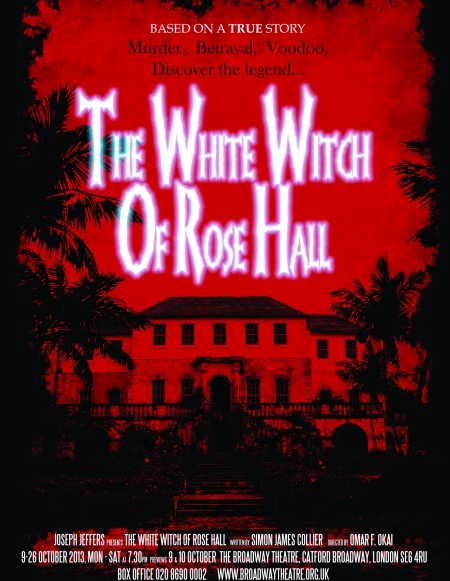

The Chilling Drama of Annie Palmer: The White Witch of Rose Hall at Broadway Theatre

A historical tale, set in the 1830s on one of Jamaica’s largest plantations. A story of power, sex and a fight for freedom, set against the backdrop of William Wilberforce’s campaign for the abolition of slavery.

The White Witch Of Rose Hall, at the Broadway Theatre, Catford, proves once again that reality can be stranger than fiction. The historical tale, set in the 1830s on one of Jamaica’s largest plantations, Rose Hall, involves a powerful plantation owner, Annie Palmer, an honourable English supporter of William Wilberforce’s abolition of slavery campaign, Robert Rutherford, and an indomitable, spirited ‘free’ black girl, Millie. The interplay between race and sexual politics that binds the characters fuels this production.

Themes of sexual jealousy and human freedom make for great drama, as writer Simon Collier’s believable characters are brought to life by a strong ensemble. Gemma Rook as Annie Palmer is a frightening figure while Tom McCarron, as the steadfastly principled Robert Rutherford, is aptly vulnerable. Alicia McKenzie’s Millie is engagingly innocent – and yet maddeningly wilful.

Robert Rutherford acts as a catalyst for emancipation when his arrival at Rose Hall precipitates a series of tragic actions, arising from the plantation workers’ sense of injustice. The slave owners exploit their power to the full, and themes of gender, race and class emerge from a brutal household, where the housekeeper is a sexual slave and the plantation owner uses male slaves for her own sexual gratification.

What playwright Simon Collier makes brilliantly clear is that even at their apparent best, the Europeans hold on to their belief of cultural supremacy: for instance, the honourable Rutherford’s treatment of Millie never once hints that he sees her as his equal. Conversely, the black slaves who are movingly characterised as dispossessed African people, show the moral compromises they are forced to make as they learn the ‘benefits’ of European civilization.

The most testing aspect of the production for me was the barbarity shown towards the slave Abraham. His torture was horrific and I confess to turning away from watching it. But I don’t think it is just squeamishness that worries me about the staging of the scene. The gruesomeness of showing teeth-pulling on stage challenges Collier’s decision to work in a naturalistic style – as there are inevitably compromises that have to be made. I couldn’t help thinking that perhaps it would have been more powerful to leave something to the imagination.

Another qualm concerned the unresolved way the play deals with magic and voodoo. History shows us how magic can be a proxy for knowledge – be it of the human anatomy, the human psyche, control of language or the laws of science – in that it can feed power. It has often (along with superstition) been a powerful tool in power struggles and subjugation. This was touched on, but the sense of magic belonging to a culture ‘other’ to European, was not given the depth it could have been. Apart from the customary voodoo doll, we were given few clues as to the powerful magic that has allowed Annie to survive three husbands and maintain her Rose Hall fiefdom. I longed to be surprised by Annie’s skill in creating in Rose Hall a place to trap her subjects and bend them to her will – something which could also have been aided by some more ambitious set design.

Despite these points of criticism, The White Witch of Rose Hall deserves good audiences and much applause. It is a vital story and a solidly good play. In the fullness of time perhaps it could grow into a great one in which the Caribbean, and Jamaica in particular, is imagined as vital to the creation of an English cultural identity.

Date reviewed: Friday 11th October 2013